- Home

- Butler, Nancy

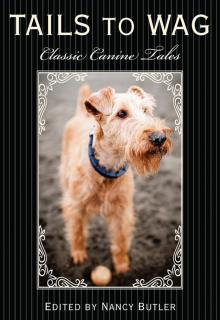

Tails to Wag

Tails to Wag Read online

Tails to Wag

Tails to Wag

Classic Canine Stories

Edited and with an Introduction by

Nancy Butler

Guilford, Connecticut

Helena, Montana

An imprint of Rowman & Littlefield

An imprint of Rowman & Littlefield

Distributed by NATIONAL BOOK NETWORK

Copyright © 2014 by Rowman & Littlefield

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, except as may be expressly permitted in writing from the publisher.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Information available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data available

ISBN 978-1-4930-0611-3 (paperback)

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

This is for my own dogs: Sparrow, aka Rutabagozers, a difficult dog but a very good basenji, and Stacy, aka Happy Dog, a cocker-Lab mix who retrieved rocks and bowling balls.

And for all the dogs I’ve known personally (or heard tall tales about): Bogie the shar pei, Brady the boxer, Murphy the golden retriever, Beorn the Norwegian elkhound, Missy the collie cross, McChesney the wire-haired fox terrier, Percy the mutt, Lobo the shepherd-husky, Max the white boxer, Cleo the dachsy mutt, Ginger Jones the cocker spaniel, Gigi and Lolita the Brittany spaniels, Lucky the setter, Oona and Oliver the greyhounds, Poncho and Fabian the chihuahuas, and Sammy Jo the Pekingese.

And for Pudgie, my father’s first dog, who followed my grandmother to church and thus became a key source of a long family tradition of storytelling.

Contents

Copyright

Introduction

Beautiful Joe (An excerpt)

By Marshall Saunders

"Uncle Dick’s Rolf"

By Georgiana M. Craik

"Ulysses and the Dogman"

By O. Henry

"The Baron’s Wonderful Dog"

By R. E. Raspe

"Brown Wolf"

By Jack London

"A Yellow Dog"

By Bret Harte

"Bingo"

By Ernest Thompson Seton

"A Dark-Brown Dog"

By Stephen Crane

"Memoirs of a Yellow Dog"

By O. Henry

"The She-Wolf"

By Saki (H. H. Munro)

"Tito: The Story of the Coyote That Learned How"

By Ernest Thompson Seton

"A Fire-fighter’s Dog"

By Arthur Quiller-Couch

"Scrap"

By Lucia Chamberlain

"Carlo, the Soldiers’ Dog"

By Rush C. Hawkins

Bruce (An excerpt)

By Albert Payson Terhune

Three Men in a Boat (An excerpt)

By Jerome K. Jerome

"Philippa’s Fox-Hunt"

By E. Somerville and Martin Ross

Bob, Son of Battle

By Alfred Ollivant

Sources

Introduction

“Humans were denied the speech of animals. The only common ground of communication upon which dogs and men can get together is in fiction.”

—O. Henry

For thousands of years, dogs have served men and women . . . as protectors of the home, hunters and retrievers of game, and guardians of the herd. But perhaps the most enduring and valued role that canines have played is that of devoted human companion. Children delight in rough–housing with dogs and adults find some reflection of their own souls in the warm, bright eyes of their favorite pet. Even the gruffest master must feel some bond of kinship at the end of the day when he relaxes with his faithful hound at his feet.

Yet in many of these classic stories, which hail from a time of an earlier, almost foreign sensibility, dogs do not always get their day. It’s difficult to believe when viewing the pampered pets on parade in any large city that dogs once had it so hard. They toiled daily in the service of their owners and were lucky if they were rewarded with an offhand pat or an old soup bone. And while some writers sentimentalize the strong bond between man and dog and others lampoon the love/hate relationship between hapless owners and clever canines, a number of these stories demonstrate the cavalier, if not downright cruel treatment dogs received. These crusading authors took up their pens to expose the frequent indifference to the plight of dogs so that people in general would look upon them with kindness and tolerance. They wanted every dog owner to gain a keener understanding of the friend who walks so faithfully at his or her side.

Focusing on the sometimes precarious relationship between human and dog, this collection begins with an excerpt from Beautiful Joe, by Marshall Saunders. This is the beloved tale of an ugly, misfit mongrel who suffers at the hands of his first owner until at last he finds a loving home. The book was written as a response to Black Beauty, which told a similar tale of a horse’s odyssey through life, withstanding ignorance and harsh treatment until he, too, finds his own green pastures. Beautiful Joe was an attempt to make readers aware of the casual mistreatment of dogs, which can be seen in “Uncle Dick’s Rolf” by Georgiana M. Craik. Even though this is a story of a dog’s loyalty and uncanny prescience, Rolf’s owner strikes out at him when the dog’s behavior grows irrational. But that does not deter Rolf from risking his own life to save Uncle Dick from the jaws of death—literally.

O. Henry, that master of the surprise ending, leaves us guessing at the end of “Ulysses and the Dogman.” It is difficult to be sure who is the pet—the bulldog on the leash or the former cowhand who walks him every night at the behest of his wealthy, citified wife. When the husband at last declares his independence, it is the dog, and not the wife, who takes the brunt of his master’s frustration.

In “The Baron’s Wonderful Dog,” a droll excerpt from R. E. Raspe’s classic, The Surprising Adventures of the Renowned Baron Munchausen, a marvelous beast exceeds her owner’s expectations—and proves that tall tales were not limited to the American West.

City life was rough on dogs in the nineteenth century. Gangs of boys tormented them, dog catchers rounded them up for extermination, and starvation lurked around every dark corner. It took a plucky dog to make his way in the urban jungle. In Stephen Crane’s “A Dark-Brown Dog,” one little mongrel has found a home in the city, but the tenement where he lives turns out to be more of a hell than a haven. The love of a child is not enough to prevent tragedy in the face of a parent’s drunken rage. On a merrier note is O. Henry’s “Memoirs of a Yellow Dog,” which tells the tale of a city dog who, along with his master, longs for the freedom of the robust, country life.

One place in America where dogs flourished was the West. Whether herding, hunting, or just going along for the ride, dogs must have found the land of wide open spaces to be something of a doggy heaven. Jack London, author of Call of the Wild and White Fang, among a host of gripping and gritty dog stories, creates a poignant tale of torn loyalties in “Brown Wolf.” Wolf is a dog with a past, but the young couple who try to tame him when he turns up wounded at their ranch, can have no way of knowing his origins. What is more puzzling are his constant attempts to run away—heading always to the north. It is only by sheerest coincidence that they discover the truth about their wandering dog, a painful truth that draws them into a contest that only the most loving and generous own

ers would agree to.

Short story author Bret Harte was known for his picaresque evocations of the denizens of the Old West. His “A Yellow Dog” is a raffish canine who is the local miscreant in the mining camp called Rattlers Ridge. The locals simultaneously revile him and brag about his exploits. When a “good woman” visits the camp, she wins over the entire male population, but are her sweet words enough to turn that “yaller” dog from his wicked ways?

From the prolific pen of Ernest Thompson Seton, who numbered among his achievements author, naturalist, illustrator, and co-founder of the Boy Scouts of America, comes the tale of “Bingo,” a dog of the West that has just a little too much adventure in his soul. Run-ins with wolves and poisoned horse carcasses don’t deter Bingo from roaming free on the Plains. Though he and his master share an uneasy partnership, in the end he is a dog who comes through for those he loves.

Even in the most spoiled lapdog, at the moment of household threat or peril to its owner, there shines the shrewd, capable eyes of the wolf. Dogs owe a great deal to their feral ancestors—the pack mentality that made them seek out and cooperate with men, the need for an alpha leader that makes them obey their human masters, and the potential for great depths of affection, which wolves regularly lavish on their mates and pups.

H. H. Munro was better known as short story master Saki. He possessed an amused and slightly skewed view of his fellow man and was the literary purveyor of casual social atrocities. In “The She-Wolf,” which might easily be called “A Lady in Wolf’s Clothing,” a pompous gentleman arouses the ire of his hostess with his constant blustering on matters metaphysical. When she coaxes a sympathetic guest at her houseparty to take part in a cunning plan to bring the braggart down a peg or two, a sugar-loving wolf named Louisa neatly steps in to complete the hoax.

“Tito: The Story of the Coyote That Learned How,” is another offering from wildlife fiction mainstay Ernest Thompson Seton. While still a pup, Tito is captured by a rancher, and quickly learns the ways of men. When her wild nature stirs, she returns to the life she was born for—taking a mate and bearing her own litter of pups. But trouble lurks nearby as an old adversary stalks Tito’s new family, and she must use all the wiles she acquired in captivity to best her enemy. This is a truly tender evocation of a wild parent and her offspring, quite unusual for the time it was written. Without anthropomorphizing Tito, the author makes her spring to life, as finely drawn and compelling as any human protagonist.

Whether it is leading the blind, aiding the disabled as a companion animal, sniffing out victims of an earthquake, escorting a patrolman on his nightly beat, or guarding the perimeter of an army camp, dogs excel in service-oriented jobs. Their intelligence, fortitude, and ability to think through dangerous situations are unquestioned, and their noble inclination is to always put their human companions first. “A Fire-fighter’s Dog,” is Arthur Quiller-Couch’s homage to a singular dog that was fascinated by fires . . . nearly as much as the men who fought them. He left a legacy of bravery in the London fire brigade he served, and even after death came to the rescue of a fireman’s widow and family.

Lucia Chamberlain’s “Scrap” is not your average stray dog—he badly wants to be part of a military company. He finds a potential advocate in salty Sergeant Muldoon, but is still unable to win over the starchy colonel, who declares that all uncollared camp dogs must be shot. It takes the combined efforts of the whole regiment to show that Scrap has “won his stripes.” Another story of a military dog is “Carlo, A Soldiers’ Dog,” a memoir by Rush C. Hawkins that follows the illustrious career of a real dog who served with the Ninth New York Volunteers during the Civil War. Although wounded in battle, Carlo, in true soldiers’ tradition, never abandoned his regiment and went on to an honorable retirement.

Albert Payson Terhune, who made Lad: A Dog into a legend of animal fiction and elevated collies to the rank of canine demigods, addresses the harsh realities of dogs going to war in “Bruce.” This excerpt deals with a group of soldiers in the trenches of World War I who have befriended a courier dog. When Bruce’s friends go reconnoitering and find themselves trapped in a pea soup–heavy fog behind German lines, he must use all his canny instincts to bring them back to safety.

There is a saying that “nobody loves their dogs like the English.” That goes likewise for the Irish, Scots, and Welsh, nationalities that have given us some of the most beloved dog breeds. The British take dogs on trains and buses and into shops and museums. Small wonder that this animal-loving nation established a society to prevent cruelty to animals before they created a similar agency to protect working children. British humorist Jerome K. Jerome clearly loves and understands dogs, but in his epic romp, Three Men in a Boat (To Say Nothing of the Dog), he gives us a waggish fox terrier named Montmorency, who is surely the wickedest dog in the whole kingdom. Focusing on Montmorency’s travails as his owner and two friends embark on a “restorative” boating trip along the Thames, this collection of excerpts must surely whet the reader’s appetite to consume the whole of Jerome’s witty and wonderful story.

Fox hunting has fallen out of favor, but when E. Somerville and Martin Ross wrote their classic Some Experiences of an Irish, R. M., it was still the rage for upper-class gents and their wives to mount up at the first cry of “Tally ho!” Yet all is not as it seems when the story’s English narrator and his new wife try to win over their Irish neighbors by taking part in “Philippa’s Fox-Hunt.” The hounds are chasing after the fox, the erstwhile hero is riding (badly) after the hounds—but what on earth is Philippa doing on that bicycle? A wry, amusing story that offers a surprisingly modern take on the “unspeakable in pursuit of the inedible,” as Oscar Wilde called fox hunting.

There are books read in childhood that linger long into adulthood and Alfred Ollivant’s Bob, Son of Battle is one such story. In the rocky dales of Yorkshire, a rogue dog called the “Black Killer” is slaying the local sheep. Two men, longtime enemies, face off, each defending his dog, each secretly fearing that the Black Killer is his own beloved pet. When the reckoning occurs, however, it is the two dogs—Ould Bob, the champion sheepdog, and Red Wull, the mongrel ruffian—who sort things out in a climax that is breathtaking and heartbreaking. In the end it is clear that nothing brings enemies together like the shared love of dogs.

These are stories to laugh over, to weep over, and to shake your head over, knowing that the nature of dogs (and their humans) has not altered in all the years since these stories were first written. Exemplars of unconditional love, dogs offer companionship without complaint and loyalty without a price. As one literary dog lover declared, “If dogs don’t go to heaven, I want to go where they go when I die.”

Beautiful Joe

(An excerpt)

Marshall Saunders

I

Only a Cur

My name is Beautiful Joe, and I am a brown dog of medium size. I am not called Beautiful Joe because I am a beauty. Mr. Morris, the clergyman, in whose family I have lived for the last twelve years, says that he thinks I must be called Beautiful Joe for the same reason that his grandfather, down South, called a very ugly colored slave-lad Cupid, and his mother Venus.

I do not know what he means by that, but when he says it people always look at me and smile. I know that I am not beautiful, and I know that I am not a thoroughbred. I am only a cur.

When my mistress went every year to register me and pay my tax, and the man in the office asked what breed I was, she said part fox-terrier and part bull-terrier; but he always put me down a cur. I don’t think she liked having him call me a cur; still, I have heard her say that she preferred curs, for they have more character than well-bred dogs. Her father said that she liked ugly dogs for the same reason that a nobleman at the court of a certain king did—namely, that no one else would.

I am an old dog now, and am writing, or rather getting a friend to write, the story of my life. I have seen my mistress laughing

and crying over a little book that she says is a story of a horse’s life, and sometimes she puts the book down close to my nose to let me see the pictures.

I love my dear mistress; I can say no more than that; I love her better than any one else in the world; and I think it will please her if I write the story of a dog’s life. She loves dumb animals, and it always grieves her to see them treated cruelly.

I have heard her say that if all the boys and girls in the world were to rise up and say that there should be no more cruelty to animals, they could put a stop to it. Perhaps it will help a little if I

tell a story. I am fond of boys and girls, and though I have seen many cruel men and women, I have seen few cruel children. I think the more stories there are written about dumb animals, the better it will be for us.

In telling my story, I think I had better begin at the first and come right on to the end. I was born in a stable on the outskirts of a small town in Maine called Fairport. The first thing I remember was lying close to my mother and being very snug and warm. The next thing I remember was being always hungry. I had a number of brothers and sisters—six in all—and my mother never had enough milk for us. She was always half starved herself, so she could not feed us properly.

I am very unwilling to say much about my early life, I have lived so long in a family where there is never a harsh word spoken, and where no one thinks of ill-treating anybody or anything, that it seems almost wrong even to think or speak of such a matter as hurting a poor dumb beast.

Tails to Wag

Tails to Wag